Download a PDF of this story here

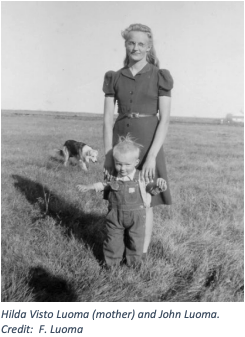

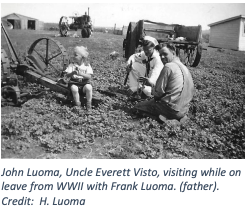

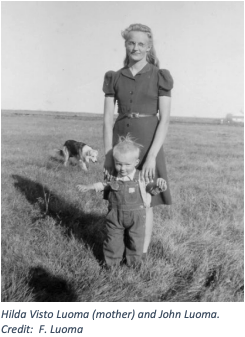

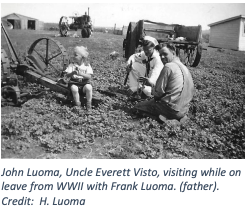

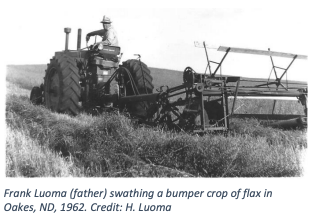

Remembering his youthful days in Oakes, North Dakota when the horse-drawn Overshot Haystacker and kerosene lamps were replaced with new hydraulic mechanics and electricity on the farm, John Luoma has always been inspired by innovation and new inventions. “In 1947, when electricity came to the farm, my mother bought new appliances – a refrigerator, a freezer and a stove-range. We had running water in the house and it seemed like things started to improve.”

This intrigue for innovation led him to a career as an engineer and a successful entrepreneur, which included designing and manufacturing the Rounder, a hydrostatic driven skid steer loader, as well as the first source separated curbside recycling system in the Twin Cities. And it is this same intrigue that has Luoma now returning to the land and planning to plant 110 acres with a continuous living cover (CLC) perennial in the summer of 2022.

planning to plant 110 acres with a continuous living cover (CLC) perennial in the summer of 2022.

Why?

With 600 acres coming up for renewal in a Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) contract, John’s part of a century-old farm, coupled with the neighbor who has farmed an additional 110 acres ready to retire, Luoma’s been considering his options. “I decided to get involved and find out what’s new in agriculture,” he said.

History on the Land

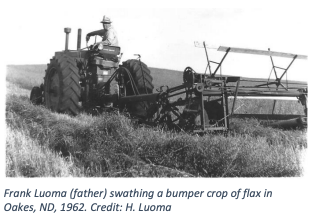

The Luoma family has enjoyed hunting and recreating on their 1,100 acres of land during annual get-togethers since his mother enrolled the farm into CRP 35 years ago. A good half of John’s land will stay in CRP. In earlier farming years, his grandparents and parents raised beef, chicken, and cattle, followed by successful stands of flax and alfalfa. The question for him is what kind of agriculture is worth bringing back into production on the land?

What Will Work on the Land

To answer that, he steps back to look at the historical picture, including what has and has not worked on the land. With the Dakota Lake aquifer being so close to the surface in Dickey County, ND, many farms over the years have dug wells and installed irrigation systems to profitably grow corn, soy, potatoes, and onions. Irrigated corn has yielded up to 300 bushels per acre and corn grown on dry land has yielded 170-190 bushels per acre, he reports. John’s land is only partially accessible to the aquifer.

To answer that, he steps back to look at the historical picture, including what has and has not worked on the land. With the Dakota Lake aquifer being so close to the surface in Dickey County, ND, many farms over the years have dug wells and installed irrigation systems to profitably grow corn, soy, potatoes, and onions. Irrigated corn has yielded up to 300 bushels per acre and corn grown on dry land has yielded 170-190 bushels per acre, he reports. John’s land is only partially accessible to the aquifer.

Moreover, he’s aware of the loss of topsoil and erosion commonly seen without cover crops on the ground. Here, he explains, many farmers don’t plant cover crops because they believe there’s not enough time to do so between annual crop seasons. “During the spring there is sand in the air; a lot of topsoil blows away until the corn and soybeans grow.” It reminds him of the conditions his grandparents and parents endured during the Dust Bowl. “We have loamy sand. It blew terribly in the 30s, 50s and last Spring, moving topsoil out of town and creating sand drifts.” Keenly aware that farming can be a risky business, Luoma’s taking a different route.

“I thought maybe perennial crops would be an answer for me. I remember the alfalfa. I remember the pastures, how well they grew. I know how well the Brome grass grows on the CRP,” he said.

Specifically, John Luoma’s interested in planting an intermediate wheatgrass known as Kernza®, a perennial grain crop with a beard-like root structure as deep as 8-12 feet. It offers him the function of a cover crop, a perennial grain and a perennial forage, which will eventually serve as hay for his neighbor’s livestock. Kernza is relatively new in North Dakota.

Why Long-Rooted Perennials?

Continuous living cover (CLC) prevents erosion by covering the ground year-round with living plants and roots. CLC crops and cropping systems can also add nutritional benefits to the soil, which can reduce the demand for fertilizers and pesticides, which are costly for farmers and can pollute surface and ground waters. Perennial crops have especially long, dense root masses that help infiltrate and retain water, which will be advantageous for Luoma’s farm. Currently, Kernza produces a harvestable grain crop for two to three years reliably, eliminating tillage during that time. Agronomists and plant breeders, in collaboration with farmers, continue to work on extending the harvestable yield beyond three years. The perennial nature of Kernza minimizes time and expense related to tillage and inputs, while increasing soil health and generating diverse revenue streams for the farmer. Further, in some environments, these roots may reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by storing carbon. These benefits accrue whether Kernza is used as a perennial forage or a perennial grain. The farmer’s choice to produce farm products using CLC provides benefits not only on-farm, but also to society and the consumer in the form of ecosystem services and other positive social and economic outcomes.

Diving Deeper Into Kernza

Research online with Green Lands Blue Waters has taught John Luoma more about the CLC concept. It’s one that incorporates perennial crops and sequences annual crops into cropping systems to maintain year-round living vegetative cover above ground and living roots below ground. CLC affords Luoma an opportunity to establish new crops on his landscape and benefit through new agricultural products for the marketplace. After learning about five different CLC approaches, as described by Green Lands Blue Waters, he’s most interested in the perennial grain and perennial forage strategies.

Research online with Green Lands Blue Waters has taught John Luoma more about the CLC concept. It’s one that incorporates perennial crops and sequences annual crops into cropping systems to maintain year-round living vegetative cover above ground and living roots below ground. CLC affords Luoma an opportunity to establish new crops on his landscape and benefit through new agricultural products for the marketplace. After learning about five different CLC approaches, as described by Green Lands Blue Waters, he’s most interested in the perennial grain and perennial forage strategies.

“Kernza is the only commercially viable new perennial crop ready to go,” he states. The perennial grain was developed and trademarked by The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, which granted Luoma permission to grow it, specifically the TLIC5 line of Kernza. The first commercially available seed variety of Kernza came out of the University of Minnesota and is called MN-Clearwater. He will grow both.

A suite of additional perennial crops is in the research and development wings at The Land Institute and University of Minnesota’s Forever Green Initiative. Both institutions work in collaboration to accomplish new perennial and winter annual cropping systems for planting across the landscape.

Mentors and Technical Assistance

The Midwest Organic and Sustainable Education Service (MOSES) referred John to Carmen Fernholz as a mentor for technical assistance. Carmen is coaching him on developing a farm plan that meets his dual-purpose objectives with Kernza for perennial grain and forage. An organic farmer who has grown Kernza for eleven years in western Minnesota, Fernholz works with many farmers who are interested in growing it. His involvement originated years ago when friend, Professor Don Wyse from the University of Minnesota, asked Fernholz if he would be interested in trying to grow Kernza in 2011. He was. And now he’s the President of Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative (PPGC), a new co-op to support Kernza growers. PPGC collaborates with commercialization team members at the University of Minnesota’s Forever Green Initiative and The Land Institute to scale up efforts and advance this type of cropping system. As a farmer, Luoma is grateful for the educational webinars, supportive policy development, and shared resources that help connect him to other farmers and interested businesses.

The Midwest Organic and Sustainable Education Service (MOSES) referred John to Carmen Fernholz as a mentor for technical assistance. Carmen is coaching him on developing a farm plan that meets his dual-purpose objectives with Kernza for perennial grain and forage. An organic farmer who has grown Kernza for eleven years in western Minnesota, Fernholz works with many farmers who are interested in growing it. His involvement originated years ago when friend, Professor Don Wyse from the University of Minnesota, asked Fernholz if he would be interested in trying to grow Kernza in 2011. He was. And now he’s the President of Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative (PPGC), a new co-op to support Kernza growers. PPGC collaborates with commercialization team members at the University of Minnesota’s Forever Green Initiative and The Land Institute to scale up efforts and advance this type of cropping system. As a farmer, Luoma is grateful for the educational webinars, supportive policy development, and shared resources that help connect him to other farmers and interested businesses.

Luoma Farm Plan

John’s neighbor, a young cattle farmer, will partner with him in this endeavor and manage 110 acres. Their farm plan begins with planting 40 acres of Kernza on prior corn land and 70 acres of hay millet. That Kernza will be harvested for hay in the fall of 2022 at an estimated 4 to 6 tons per acre. After the hay millet is harvested, they’ll plant another 70 acres of Kernza in mid-August, which should be harvestable as a grain the following summer. At that point in the season, Kernza can continue to grow as a forage through November.

Government Cost Share Support for Planting Kernza

Meanwhile, Luoma’s discovered the challenge of navigating cost share support for planting Kernza through local, state, and federal government programs. He has applied for government support through North Dakota’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), but expects to be only partially reimbursed for the crop rotation and nutrition management aspects of his efforts. To date, Kernza does not qualify for federal crop insurance.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service hosts two relevant programs with funding pools that could serve as a home for planting Kernza: the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). These programs focus on improving water quality, soil health, and address many agricultural resource concerns. Each state currently ranks and allocates their EQIP and CSP support of practices, individually, based on input from local working groups, farmer demand, and technical committees.

A more cohesive regional strategy is needed to navigate NRCS practice prioritization in order to optimize more support for planting CLC farming systems, including Kernza, in the Upper Mississippi River Basin.

The Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative and the Developing Market

As an entrepreneur who brings a long record of success, Luoma still considers growing Kernza to be a smart business investment in North Dakota. This is primarily due to the new cooperative. PPGC offers him marketing support and analysis, pricing structure, and access to current research. “This is a business venture, as I see it,” says Luoma. “I would not consider doing this without that co-op.” He remembers the vital role that the supply co-operative in Oakes played for his father, who was on the board and one of its founding members.

“Our marketing support is probably the number one reason why most of the growers are becoming part of the co-op,” says Fernholz. “If they are going to grow the crop, they need to be relatively assured that there will in fact be a market.” In its early stage of development, the Kernza market serves a niche mix of businesses. A newly hired marketer for the co-op, Alex Heilman, of Mad AG, is making inroads for the Kernza market with increased corporate interest along with smaller entrepreneurial customers. Director of Marketing Development for the Forever Green Initiative, Connie Carlson, points to the University of Minnesota’s unique platform of its own commercialization team actively introducing this new crop and building out its markets. “It’s been fifty years since the last launch of a major crop. The soybean was the last one,” she said. She continues to identify potential Kernza buyers and end users.

The Demand

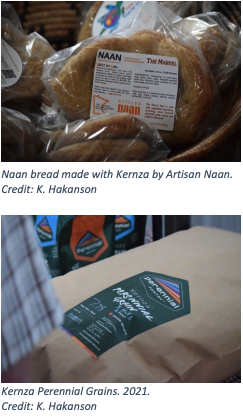

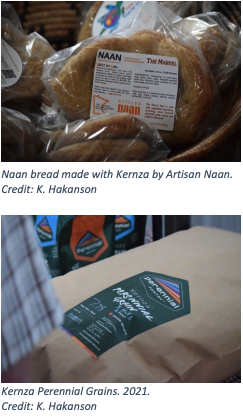

Current demand for Kernza includes Patagonia Provisions’ new organic Kernza® Fusilli pasta, a pale ale, an IPA and a Belgian-style Wit beer named Long Root® by Patagonia and Hopworks Urban Brewery in Oregon; a variety of Kernza ales by Bang Brewing and Dual Citizen in St. Paul; and a Regenerative Whole Grain Flour blend, Perennial Pancake and Waffle Mix, and 100% Kernza flour from Perennial Pantry. General Mill’s Cascadian Farms Organic Climate Smart Kernza Grains Cereal is available at select Whole Foods stores across the country including those in Madison, Wisconsin, St. Paul, Minnesota, Columbus, Ohio, and Bend, Oregon. A St. Cloud, Minnesota baker selling her Kernza naan and pita pockets through Lunds Byerly stores in the Twin Cities under the name Artisan Naan, has plans to expand. Interest is on the rise among brewers, distillers, bakeries, restaurants, and school districts as well.

Current demand for Kernza includes Patagonia Provisions’ new organic Kernza® Fusilli pasta, a pale ale, an IPA and a Belgian-style Wit beer named Long Root® by Patagonia and Hopworks Urban Brewery in Oregon; a variety of Kernza ales by Bang Brewing and Dual Citizen in St. Paul; and a Regenerative Whole Grain Flour blend, Perennial Pancake and Waffle Mix, and 100% Kernza flour from Perennial Pantry. General Mill’s Cascadian Farms Organic Climate Smart Kernza Grains Cereal is available at select Whole Foods stores across the country including those in Madison, Wisconsin, St. Paul, Minnesota, Columbus, Ohio, and Bend, Oregon. A St. Cloud, Minnesota baker selling her Kernza naan and pita pockets through Lunds Byerly stores in the Twin Cities under the name Artisan Naan, has plans to expand. Interest is on the rise among brewers, distillers, bakeries, restaurants, and school districts as well.

Mad Ag and research firm, Informa, are working on market analysis reports for the co-op to inform members’ understanding of Kernza supply and demand and project revenues in several scenarios.

Researcher Relationships with PPGC Growers

Growers in several states plan to work together with agronomists and plant breeders from the University of Minnesota in a mutually beneficial way. “They can give us new varietal types and we can feed back to them agronomic challenges and other data that we find while growing the crop in our fields,” explains Fernholz. This type of support is welcomed by John Luoma.

Additional agronomic support for Luoma will come from the North Dakota State University Extension Agronomist, Dr. Clair Keene. During her time at the Williston Research Extension Center (WREC), she started a small Kernza seed increase in partnership with The Land Institute, working with Tessa Peters, Director of Crop Stewardship, to obtain licensing. Luoma will purchase this seed from WREC. For the past three years, Keene has managed Kernza variety trials at Williston with lines from The Land Institute and the University of Minnesota. “These trials have been a good opportunity to see how Kernza performs in western North Dakota,” said Keene.

Membership in PPGC Grows

Since the Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative incorporated last summer, twenty-eight members have joined and an estimated eighteen growers expect to be harvesting Kernza by this fall on approximately 1,500 acres. With the current interest, growers could potentially double by the end of 2022, reports Fernholz. Future avenues of support from the co-op include potentially licensing the seed and exclusive varieties, supply management, and bringing post-harvest infrastructure online for the de-hulling, sorting, and cleaning grain. Should additional autonomous co-ops like PPGC develop across the country, the co-creation of a marketing agency in common would facilitate supportive communications among them, including establishing similar pricing, projects Fernholz. Nationwide, nearly 4,000 acres of Kernza have been planted to date.

Since the Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative incorporated last summer, twenty-eight members have joined and an estimated eighteen growers expect to be harvesting Kernza by this fall on approximately 1,500 acres. With the current interest, growers could potentially double by the end of 2022, reports Fernholz. Future avenues of support from the co-op include potentially licensing the seed and exclusive varieties, supply management, and bringing post-harvest infrastructure online for the de-hulling, sorting, and cleaning grain. Should additional autonomous co-ops like PPGC develop across the country, the co-creation of a marketing agency in common would facilitate supportive communications among them, including establishing similar pricing, projects Fernholz. Nationwide, nearly 4,000 acres of Kernza have been planted to date.

Pricing

In today’s scenario as a PPGC grower of Kernza, pricing matters. Due diligence is being taken to make sure these growers can actually thrive. Early adopters, like Luoma in North Dakota, who are taking on risk to create favorable outcomes for rebuilding the soil, restoring the quality of public waters, and storing carbon, also need to make a return on their investment. The costs of the land, the machinery, the labor, and the seed contribute to their variable and fixed costs, per Fernholz, but most importantly, the value of growing Kernza is the ecosystem services the farmer is contributing through this choice. What is the value of stored carbon, cleaner water, healthy soil to the society and to the consumer? He believes these values should be reflected in its price.

Determining the price is a work in progress, said Fernholz, and the subject of several research projects underway. The coming years will be critical for price stabilization, which will be informed by growers, buyers, and consumers revealing their willingness to pay.

Kernza’s yield in usable pounds – meaning grains ready to be added to food after dehulling, separating the chaff, sorting out broken kernels, and cleaning – is estimated at 250-400 pounds per acre currently. According to Colin Cureton, Director of Adoption and Scaling with the Forever Green Initiative, prices since the 2021 harvest for bulk food grade grain have been $2.50-$5.50 per pound. Fernholz shared that PPGC’s current price range is $4.00-6.50 per pound, depending on production system.

Luoma believes he’ll have plenty of forage to more than cover his costs, whether the grain succeeds or not. He wants this to do well, however, particularly for his neighbors. His new partner has two young sons, aged 12 and 14, who recently told their parents they are interested in being farmers. Another nearby farmer in the county will rent Luoma a modern 7-½” air-seeder. After swathing and drying the Kernza, another neighbor will combine the crop with his 45-foot header combine. When it’s time to cut it down and bale the straw, another neighbor who has a custom farming service will help them cut their 2 tons per acre of straw. This straw will either serve as feed for his partner’s cattle or will be sold. Not one of these neighbors is familiar with Kernza, but Luoma can see how its value might just ripple through the farming community around his home town of Oakes, North Dakota.

Innovating for the Future on the Land

Through the presence of the co-op in his youth, John learned about issues related to all aspects of farming. He fondly recalls the social life enjoyed by co-op members. Through his mother’s encouragement to pursue an education, he left his hometown roots for new cultural experiences in other countries – first as a foreign exchange student on two farms in England, followed by membership in the initial class of President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps. He was the first in his family to graduate from high school and obtain higher education degrees in engineering and business. Opportunities followed resulting from hard work and his willingness to take on risk. Today, he is drawn to his home roots, honoring his family’s legacy of farming and affirming his ties to the land and belief in its future. Luoma believes that planting perennial crops like Kernza is the way forward for him and for his neighbors. He hopes to expand these efforts in the future.

Through the presence of the co-op in his youth, John learned about issues related to all aspects of farming. He fondly recalls the social life enjoyed by co-op members. Through his mother’s encouragement to pursue an education, he left his hometown roots for new cultural experiences in other countries – first as a foreign exchange student on two farms in England, followed by membership in the initial class of President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps. He was the first in his family to graduate from high school and obtain higher education degrees in engineering and business. Opportunities followed resulting from hard work and his willingness to take on risk. Today, he is drawn to his home roots, honoring his family’s legacy of farming and affirming his ties to the land and belief in its future. Luoma believes that planting perennial crops like Kernza is the way forward for him and for his neighbors. He hopes to expand these efforts in the future.

Author Anne Queenan, Queenan Productions

anne@queenanproductions.com

Anne Queenan writes and produces stories that inform and engage on subjects interweaving land stewardship, agriculture, science, clean water, and collaborative communities. She brings to life sweet spots of hope and curiosity with real life scenarios sharpened through her expertise in public broadcasting and communications. Her social work training amplifies the human voice and points to interconnections where systemic change can happen. She has written, produced, and developed documentary short videos, articles, and communications strategy for foundations, environmental nonprofits, state agencies, educational institutions, and soil and water conservation districts. She has also co-led and organized steering and advisory committees for cocreative outreach efforts in water quality with diverse partners. Queenan is also a photographer, videographer, and drone operator. She and her dog, Coda, live on the Mississippi River in the Driftless Area, where she enjoys paddling, birding, and hiking through the Bluffs.

Anne Queenan writes and produces stories that inform and engage on subjects interweaving land stewardship, agriculture, science, clean water, and collaborative communities. She brings to life sweet spots of hope and curiosity with real life scenarios sharpened through her expertise in public broadcasting and communications. Her social work training amplifies the human voice and points to interconnections where systemic change can happen. She has written, produced, and developed documentary short videos, articles, and communications strategy for foundations, environmental nonprofits, state agencies, educational institutions, and soil and water conservation districts. She has also co-led and organized steering and advisory committees for cocreative outreach efforts in water quality with diverse partners. Queenan is also a photographer, videographer, and drone operator. She and her dog, Coda, live on the Mississippi River in the Driftless Area, where she enjoys paddling, birding, and hiking through the Bluffs.

planning to plant 110 acres with a continuous living cover (CLC) perennial in the summer of 2022.

planning to plant 110 acres with a continuous living cover (CLC) perennial in the summer of 2022. To answer that, he steps back to look at the historical picture, including what has and has not worked on the land. With the Dakota Lake aquifer being so close to the surface in Dickey County, ND, many farms over the years have dug wells and installed irrigation systems to profitably grow corn, soy, potatoes, and onions. Irrigated corn has yielded up to 300 bushels per acre and corn grown on dry land has yielded 170-190 bushels per acre, he reports. John’s land is only partially accessible to the aquifer.

To answer that, he steps back to look at the historical picture, including what has and has not worked on the land. With the Dakota Lake aquifer being so close to the surface in Dickey County, ND, many farms over the years have dug wells and installed irrigation systems to profitably grow corn, soy, potatoes, and onions. Irrigated corn has yielded up to 300 bushels per acre and corn grown on dry land has yielded 170-190 bushels per acre, he reports. John’s land is only partially accessible to the aquifer. Research online with Green Lands Blue Waters has taught John Luoma more about the CLC concept. It’s one that incorporates perennial crops and sequences annual crops into cropping systems to maintain year-round living vegetative cover above ground and living roots below ground. CLC affords Luoma an opportunity to establish new crops on his landscape and benefit through new agricultural products for the marketplace. After learning about five different CLC approaches, as described by Green Lands Blue Waters, he’s most interested in the perennial grain and perennial forage strategies.

Research online with Green Lands Blue Waters has taught John Luoma more about the CLC concept. It’s one that incorporates perennial crops and sequences annual crops into cropping systems to maintain year-round living vegetative cover above ground and living roots below ground. CLC affords Luoma an opportunity to establish new crops on his landscape and benefit through new agricultural products for the marketplace. After learning about five different CLC approaches, as described by Green Lands Blue Waters, he’s most interested in the perennial grain and perennial forage strategies. The Midwest Organic and Sustainable Education Service (MOSES) referred John to Carmen Fernholz as a mentor for technical assistance. Carmen is coaching him on developing a farm plan that meets his dual-purpose objectives with Kernza for perennial grain and forage. An organic farmer who has grown Kernza for eleven years in western Minnesota, Fernholz works with many farmers who are interested in growing it. His involvement originated years ago when friend, Professor Don Wyse from the University of Minnesota, asked Fernholz if he would be interested in trying to grow Kernza in 2011. He was. And now he’s the President of Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative (PPGC), a new co-op to support Kernza growers. PPGC collaborates with commercialization team members at the University of Minnesota’s Forever Green Initiative and The Land Institute to scale up efforts and advance this type of cropping system. As a farmer, Luoma is grateful for the educational webinars, supportive policy development, and shared resources that help connect him to other farmers and interested businesses.

The Midwest Organic and Sustainable Education Service (MOSES) referred John to Carmen Fernholz as a mentor for technical assistance. Carmen is coaching him on developing a farm plan that meets his dual-purpose objectives with Kernza for perennial grain and forage. An organic farmer who has grown Kernza for eleven years in western Minnesota, Fernholz works with many farmers who are interested in growing it. His involvement originated years ago when friend, Professor Don Wyse from the University of Minnesota, asked Fernholz if he would be interested in trying to grow Kernza in 2011. He was. And now he’s the President of Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative (PPGC), a new co-op to support Kernza growers. PPGC collaborates with commercialization team members at the University of Minnesota’s Forever Green Initiative and The Land Institute to scale up efforts and advance this type of cropping system. As a farmer, Luoma is grateful for the educational webinars, supportive policy development, and shared resources that help connect him to other farmers and interested businesses. Current demand for Kernza includes Patagonia Provisions’ new organic Kernza® Fusilli pasta, a pale ale, an IPA and a Belgian-style Wit beer named Long Root® by Patagonia and Hopworks Urban Brewery in Oregon; a variety of Kernza ales by Bang Brewing and Dual Citizen in St. Paul; and a Regenerative Whole Grain Flour blend, Perennial Pancake and Waffle Mix, and 100% Kernza flour from Perennial Pantry. General Mill’s Cascadian Farms Organic Climate Smart Kernza Grains Cereal is available at select Whole Foods stores across the country including those in Madison, Wisconsin, St. Paul, Minnesota, Columbus, Ohio, and Bend, Oregon. A St. Cloud, Minnesota baker selling her Kernza naan and pita pockets through Lunds Byerly stores in the Twin Cities under the name Artisan Naan, has plans to expand. Interest is on the rise among brewers, distillers, bakeries, restaurants, and school districts as well.

Current demand for Kernza includes Patagonia Provisions’ new organic Kernza® Fusilli pasta, a pale ale, an IPA and a Belgian-style Wit beer named Long Root® by Patagonia and Hopworks Urban Brewery in Oregon; a variety of Kernza ales by Bang Brewing and Dual Citizen in St. Paul; and a Regenerative Whole Grain Flour blend, Perennial Pancake and Waffle Mix, and 100% Kernza flour from Perennial Pantry. General Mill’s Cascadian Farms Organic Climate Smart Kernza Grains Cereal is available at select Whole Foods stores across the country including those in Madison, Wisconsin, St. Paul, Minnesota, Columbus, Ohio, and Bend, Oregon. A St. Cloud, Minnesota baker selling her Kernza naan and pita pockets through Lunds Byerly stores in the Twin Cities under the name Artisan Naan, has plans to expand. Interest is on the rise among brewers, distillers, bakeries, restaurants, and school districts as well. Since the Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative incorporated last summer, twenty-eight members have joined and an estimated eighteen growers expect to be harvesting Kernza by this fall on approximately 1,500 acres. With the current interest, growers could potentially double by the end of 2022, reports Fernholz. Future avenues of support from the co-op include potentially licensing the seed and exclusive varieties, supply management, and bringing post-harvest infrastructure online for the de-hulling, sorting, and cleaning grain. Should additional autonomous co-ops like PPGC develop across the country, the co-creation of a marketing agency in common would facilitate supportive communications among them, including establishing similar pricing, projects Fernholz. Nationwide, nearly 4,000 acres of Kernza have been planted to date.

Since the Perennial Promise Growers Cooperative incorporated last summer, twenty-eight members have joined and an estimated eighteen growers expect to be harvesting Kernza by this fall on approximately 1,500 acres. With the current interest, growers could potentially double by the end of 2022, reports Fernholz. Future avenues of support from the co-op include potentially licensing the seed and exclusive varieties, supply management, and bringing post-harvest infrastructure online for the de-hulling, sorting, and cleaning grain. Should additional autonomous co-ops like PPGC develop across the country, the co-creation of a marketing agency in common would facilitate supportive communications among them, including establishing similar pricing, projects Fernholz. Nationwide, nearly 4,000 acres of Kernza have been planted to date. Through the presence of the co-op in his youth, John learned about issues related to all aspects of farming. He fondly recalls the social life enjoyed by co-op members. Through his mother’s encouragement to pursue an education, he left his hometown roots for new cultural experiences in other countries – first as a foreign exchange student on two farms in England, followed by membership in the initial class of President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps. He was the first in his family to graduate from high school and obtain higher education degrees in engineering and business. Opportunities followed resulting from hard work and his willingness to take on risk. Today, he is drawn to his home roots, honoring his family’s legacy of farming and affirming his ties to the land and belief in its future. Luoma believes that planting perennial crops like Kernza is the way forward for him and for his neighbors. He hopes to expand these efforts in the future.

Through the presence of the co-op in his youth, John learned about issues related to all aspects of farming. He fondly recalls the social life enjoyed by co-op members. Through his mother’s encouragement to pursue an education, he left his hometown roots for new cultural experiences in other countries – first as a foreign exchange student on two farms in England, followed by membership in the initial class of President John F. Kennedy’s Peace Corps. He was the first in his family to graduate from high school and obtain higher education degrees in engineering and business. Opportunities followed resulting from hard work and his willingness to take on risk. Today, he is drawn to his home roots, honoring his family’s legacy of farming and affirming his ties to the land and belief in its future. Luoma believes that planting perennial crops like Kernza is the way forward for him and for his neighbors. He hopes to expand these efforts in the future.

The second corn crop came in at slightly over 200 bushels per acre. “I was gobsmacked, to say the least,” says Mark. “It was unbelievable.”

The second corn crop came in at slightly over 200 bushels per acre. “I was gobsmacked, to say the least,” says Mark. “It was unbelievable.”

This fact sheet is a joint effort based on the

This fact sheet is a joint effort based on the  Prairie strips are small areas of diverse native grasses and wildflowers incorporated into row crop fields. Their deep roots hold soil in place even in heavy rain, helping to protect soil and water quality while providing habitat for birds and pollinators. Prairie strips can be situated within fields or as filter strips at the edges, with the width adjusted based on slope and expected amount of water flow.

Prairie strips are small areas of diverse native grasses and wildflowers incorporated into row crop fields. Their deep roots hold soil in place even in heavy rain, helping to protect soil and water quality while providing habitat for birds and pollinators. Prairie strips can be situated within fields or as filter strips at the edges, with the width adjusted based on slope and expected amount of water flow.

limited to online learning. For Gavi, this meant a break from studying mechanical engineering and earth plant science at Yale University. For Remi, it was neuroscience and dance at Middlebury College. After recalibrating and doing quite a bit of research, they forged a different path. Honoring their family, their roots in Judaism, and their desire to work towards a more regenerative agriculture, agroforestry plans were initiated to restore the soil and draw down carbon on the sixth generation family farm – one that had been growing corn and soybeans for more than six decades.

limited to online learning. For Gavi, this meant a break from studying mechanical engineering and earth plant science at Yale University. For Remi, it was neuroscience and dance at Middlebury College. After recalibrating and doing quite a bit of research, they forged a different path. Honoring their family, their roots in Judaism, and their desire to work towards a more regenerative agriculture, agroforestry plans were initiated to restore the soil and draw down carbon on the sixth generation family farm – one that had been growing corn and soybeans for more than six decades.

Five Acres of a Food Forest

Five Acres of a Food Forest Biochar is being studied as an amendment that may increase the rate of carbon sequestration. The apprentices at Zumwalt Acres are learning how to measure the carbon captured through using research methods, like fluxing. Biochar also may increase soil productivity. The resulting enhancement of plant growth could in turn absorb more carbon dioxide. According to the NRCS, biochar helps reduce bulk density, runoff, soil loss, and the leaching of nitrogen. It also increases porosity, infiltration, and improves the soil’s ability to resist rainfall impact, water and wind erosion.

Biochar is being studied as an amendment that may increase the rate of carbon sequestration. The apprentices at Zumwalt Acres are learning how to measure the carbon captured through using research methods, like fluxing. Biochar also may increase soil productivity. The resulting enhancement of plant growth could in turn absorb more carbon dioxide. According to the NRCS, biochar helps reduce bulk density, runoff, soil loss, and the leaching of nitrogen. It also increases porosity, infiltration, and improves the soil’s ability to resist rainfall impact, water and wind erosion. Linda Meschke has over 35 years of experience in working on agricultural and water resource issues in south central Minnesota. Her work has been focused on projects that improve rural communities and the implementation of a variety of conservation practices and getting changes on the landscape to improve water quality. She is currently working on landscape diversification of the intense corn and soybean region in south central Minnesota to integrate more perennials and 3rd Crops and to develop agriculture-related entrepreneurial enterprises.

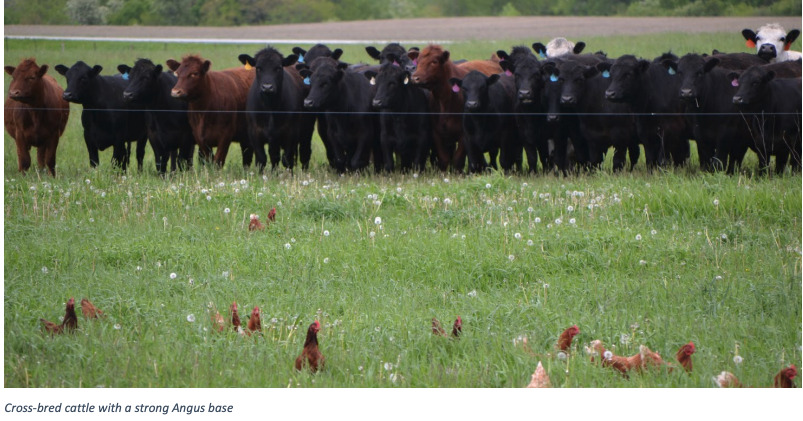

Linda Meschke has over 35 years of experience in working on agricultural and water resource issues in south central Minnesota. Her work has been focused on projects that improve rural communities and the implementation of a variety of conservation practices and getting changes on the landscape to improve water quality. She is currently working on landscape diversification of the intense corn and soybean region in south central Minnesota to integrate more perennials and 3rd Crops and to develop agriculture-related entrepreneurial enterprises. Bruce Carney and his wife, Connie, began their fulltime farming enterprise, Carney Family Farms, when Bruce’s father passed away in the spring of 1996. Corn, soybeans and a cow/calf herd had historically been produced here. In early 2000, Carney started transitioning from row crops to forage-finished beef. The last year for row crop acreage was 2008. By then, the transition to the forage-finished beef operation was complete, perennial-based with pastures, forages, and a cow/calf operation.

Bruce Carney and his wife, Connie, began their fulltime farming enterprise, Carney Family Farms, when Bruce’s father passed away in the spring of 1996. Corn, soybeans and a cow/calf herd had historically been produced here. In early 2000, Carney started transitioning from row crops to forage-finished beef. The last year for row crop acreage was 2008. By then, the transition to the forage-finished beef operation was complete, perennial-based with pastures, forages, and a cow/calf operation.

Carney is working through EQIP to add warm season native perennial grasses, forbs, and legumes into 80 acres on his home farm. This will help extend the forage availability in the summer season for his herd and complement his cool season grasses and forages. Interseeding summer forages helps reduce weed pressure and cool season perennial seedbank competition before the warm season grasses are seeded.

Carney is working through EQIP to add warm season native perennial grasses, forbs, and legumes into 80 acres on his home farm. This will help extend the forage availability in the summer season for his herd and complement his cool season grasses and forages. Interseeding summer forages helps reduce weed pressure and cool season perennial seedbank competition before the warm season grasses are seeded.

Silvopasture, a practice of agroforestry, integrates a variety of trees, forages, and managed grazing of livestock in a mutually beneficial way. The trees provide shade for livestock and serve as windbreaks in the pasture. This is something that Bruce is also looking into for the future.

Silvopasture, a practice of agroforestry, integrates a variety of trees, forages, and managed grazing of livestock in a mutually beneficial way. The trees provide shade for livestock and serve as windbreaks in the pasture. This is something that Bruce is also looking into for the future.

Scott also farms strip-tilled corn and cover crops in the rich soils near Blue Earth, Minnesota. From a conventional corn-soybean crop rotation, he is transitioning to a farming system that uses regenerative practices including continuous living cover. Rather than focus on yield, his priority is on farm profitability.

Scott also farms strip-tilled corn and cover crops in the rich soils near Blue Earth, Minnesota. From a conventional corn-soybean crop rotation, he is transitioning to a farming system that uses regenerative practices including continuous living cover. Rather than focus on yield, his priority is on farm profitability. (EQIP) to support trying these practices on his land.

(EQIP) to support trying these practices on his land.